From the burnout archive

Six years ago this week, my academic career fell apart. A lesson plan from that time points to how burnout affects the brain.

January was wild. The End of Burnout was released at the beginning of the month, and from then until the end of it, I did twenty interviews about the book, for media on three continents. Two big highlights were the Commonweal magazine podcast and KERA Think, a radio show from my local NPR affiliate. I’ve been a longtime listener to both shows, and I was honored to appear on them. In fact, I was surprised by how nervous I was in speaking to Think host Krys Boyd, whose voice is so familiar. Maybe it was because I knew my neighbors were listening (and judging).

In addition, I wrote an article for the job site The Muse titled, “No, You Didn’t Cause Your Own Burnout.” And I was featured in an article on work-life balance in Outside magazine (paywalled, sorry).

Faculty groups at Concordia College and Wake Forest University are discussing The End of Burnout. (Perhaps your workplace or book club would like to do the same?) And I did a speaking event for Concordia, which you can view here.

I also got to speak with my longtime friend Jacqueline Bussie of the Collegeville Institute, which greatly helped me write the book.

The audio version of the book is now available from Audible. I have a few free downloads I can share; I think I’ll do a giveaway next newsletter.

Thanks to all of you who have rated and reviewed the book on Amazon! (No thanks to whoever gave it one star.) It helps a lot. If you’ve read the book, please consider leaving a review.

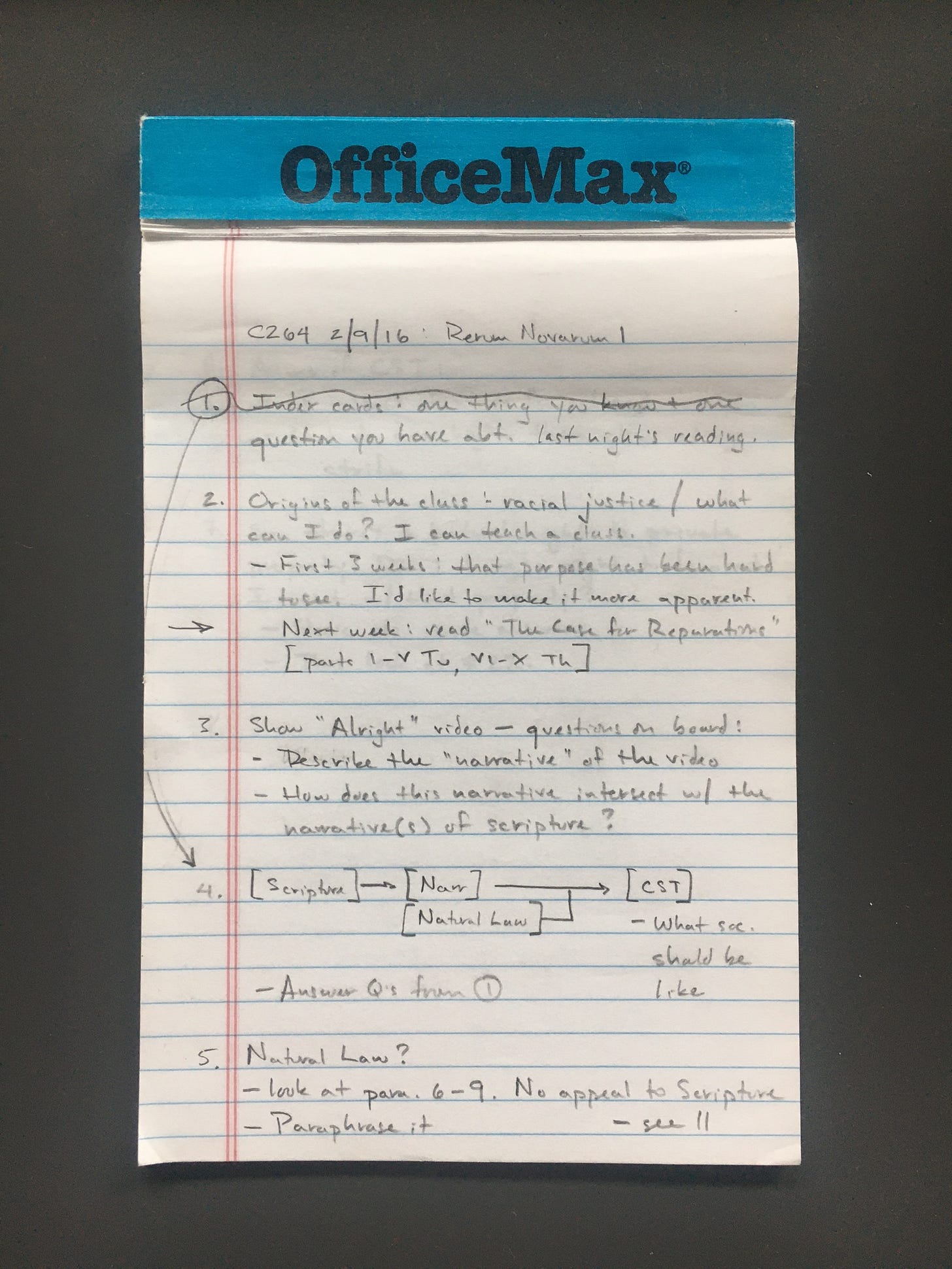

In the introduction to The End of Burnout, I share a scene from my classroom on the day I realized my dream of being a college professor had fallen apart. That day was six years ago this week. A couple months ago, I happened upon the lesson plan from that class session. Here it is:

The person who wrote this plan wasn’t in total despair yet. (By the end of class, though, he was.) This was about three weeks into the semester, and I still believed I could sustain my career. But I wrote the lesson on a 5” x 7” pad, which to me is a highly impermanent medium. It’s for jotting down ephemera, not keeping a permanent record. I think it’s purely accidental that I held onto it. Later that semester, I would start keeping lesson plans on 3x5 cards and Post-It notes, then throw them away once class ended. All I needed to do was survive the class session, not bring my store of pedagogical wisdom to bear on the moment.

I have always favored hand-writing my lesson plans, even when I’m recycling a past semester’s lesson. Writing it out helps me process what I want to do in the class ahead. Early in my career, I wrote the notes on a legal pad, punched holes in them, and then placed them in a binder. By the end, everything became more haphazard.

Burnout harms your brain’s executive function: your ability to plan, process information, regulate emotions, and make decisions. When you’re burned out, you don’t just feel tired; you get worse at your job. This is one reason why I don’t entirely buy narratives of burnout in which the person continues to excel on the job. It can be an attempt to have it both ways: to be an exhausted martyr to your work and to still be a top performer.

(I should add, though, that exhaustion is on the burnout spectrum, a partial form of the syndrome. Exhaustion can certainly be a gateway to a much worse experience of burnout.)

In the depths of my burnout, planning for class was a frustrating, unbearable chore. My mind felt blank. I had been teaching for years and years but couldn’t unlock my store of pedagogical knowledge. As a result, I wasn’t as good a teacher as I once had been.

It’s tempting to say of burned-out nurses, doctors, and teachers that they are struggling through difficult conditions and still doing a great job, as if their burnout were only a problem for themselves, as if all we need to do is feel bad for these heroes. But in fact, if they’re burned out, then they aren’t doing a great job. And when their job performance suffers, a lot of other people suffer, too.

Your burnout isn’t your fault, and it isn’t only your problem. Everyone plays a role in the causes, and everyone bears the cost of its effects. That’s why a solution to burnout has to be undertaken by society as a whole.

I’ll close with a few reading recommendations.

I felt appropriately challenged by two essays on work and the creative life: Meghan O’Gieblyn’s “Routine Maintenance” in Harper’s and Apoorva Tadepalli’s “Careerism” in The Point. I greatly admire both of these writers, and when I read these essays within a couple days of each other, I found remarkable resonance between them. Together, they’re arguing that creative work like writing remains work, even when it’s enjoyable, and even after “they figured it out: / that we’re gonna do it anyway, even if it doesn’t pay,” as Gillian Welch put it in what must have been one of the first songs about the creative economy in the digital age.

O’Gieblyn and Tadepalli suggest that there will never a post-work era; most people, artists included, crave the discipline and the sometimes-mystical experience of work, even when we don’t strictly have to do it. I’d like to engage these essays more fully sometime. (O’Gieblyn’s is about habits, but it’s also about monks and technology, so you know I was into it.)

And I loved this article in the Washington Post about how the monks of the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, who are a major focus of chapter 7 in the book, weathered the pandemic by isolating themselves even more than normal, which is saying a lot, given that they live in a remote canyon, 13 miles down a dirt road from the nearest highway. The result: not one monk has ever tested positive for Covid. Now they’re about to open back up for guests (and much-needed income).