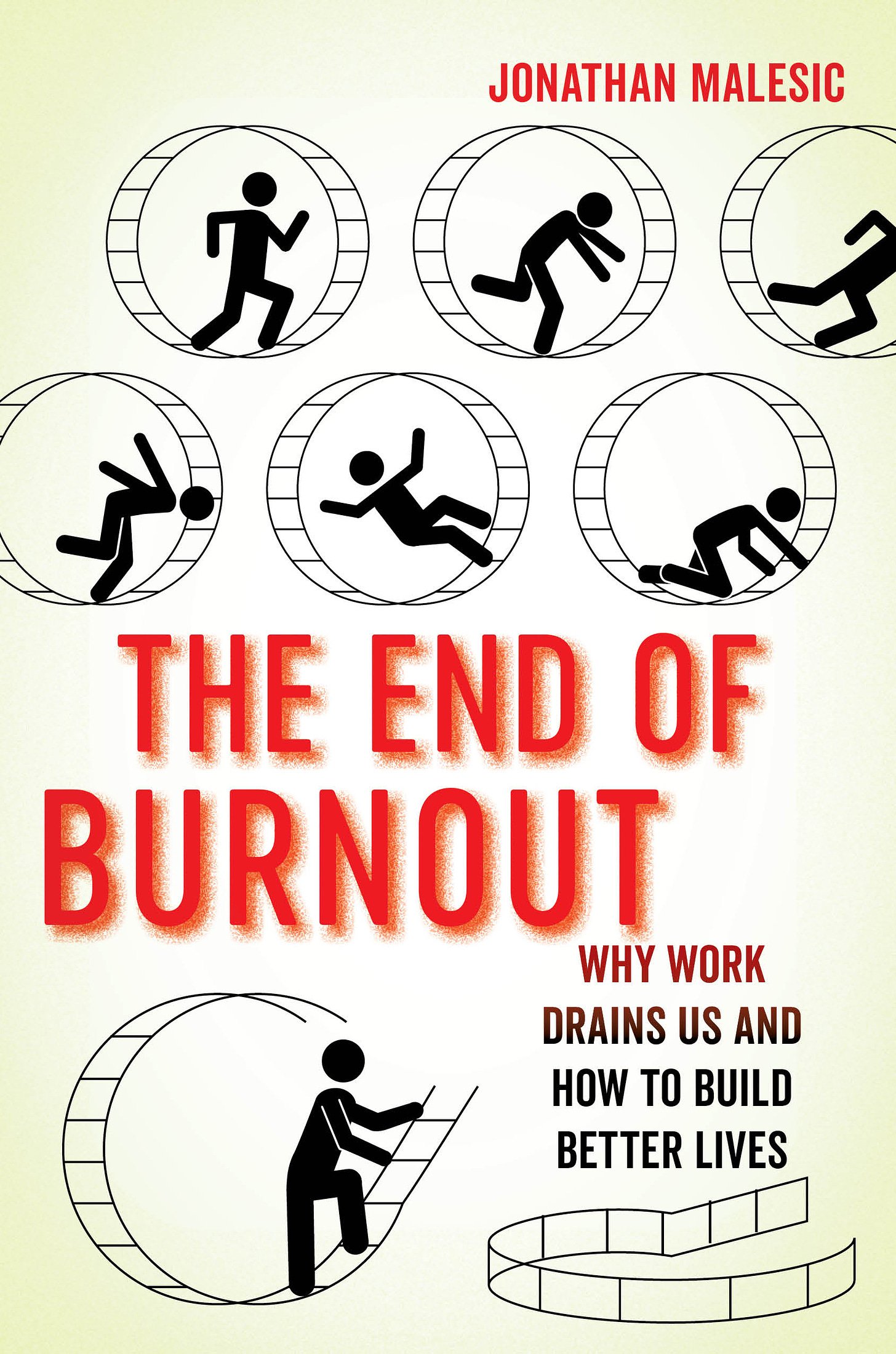

My burnout book — now officially titled, The End of Burnout — took some key steps in becoming real recently. I was so thrilled when my editor at University of California Press sent me the cover:

Admit it: If you saw that on a bookstore shelf, you would buy it. You want to be the person breaking through the wheel. The cover reminds me of Max Weber’s image of the work ethic as an “iron cage” at the end of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

But it also reminds me of an image from Simone Weil’s fragmentary essay, “The Mysticism of Work”:

A squirrel turning in its cage and the rotation of the celestial sphere — extreme misery and extreme grandeur.

It is when man sees himself as a squirrel turning round and round in a circular cage that, if he does not lie to himself, he is close to salvation.

Weil is somewhat more optimistic than I am about the possibilities routine, fruitless work can bring. In her eyes, the universe itself turns around and around for no apparent reason, and liberation is not to be found in breaking out of it but if living into the repetition more fully. I admit that, though I tend to think salvation, religious or secular, is more about escaping labor, I am also drawn to the idea that there is liberation within work’s endless futility. “One must imagine Sisyphus happy” and all that.

The book still has a ways to go before it’s ready for sale in November. As soon as it’s ready for preorder, believe me, I will let you know. For now, you might think about which of the stick figures best represents you at this moment.

After a long period without publishing much, I had a few things come out recently:

A review of Sarah Jaffe’s new book, Work Won’t Love You Back, for The New Republic. Jaffe is one of the best labor journalists out there, and in this book she surveys what the imperative to “love what you do” has done to workers across industries over the past 30-40 years. What I found most interesting was how the love ethos is not only a means for employers to extract more labor from worker for less pay, but also something workers can use to organize for better working conditions, if only they direct their love to each other instead of to the job itself. One of the most interesting chapters of the book focuses on athletes, and especially on women professional hockey players. As a big hockey fan, I was envoius of Jaffe for getting to interview (now-retired) U.S. national team captain Meghan Duggan. Like the U.S. women’s national soccer team, the hockey team is the best in world (they’ve dominated the world champtionships, though Canada has dominated the Olympic Games recently), and the players have successfuly organized to win better conditions for themselves. Even so, it’s shocking to see how hard these professionals work, and for how little monetary reward. Here again is my review essay: https://newrepublic.com/article/161005/dont-love-job-sarah-jaffe-book-review.

A review of Paul Griffiths’s new book, Regret: A Theology, for Commonweal. As longtime readers of this newsletter know, I’m a big fan of regret. (I wrote about the value of regret last year for The Hedgehog Review.) I see regret as a way to reconcile our past and present selves, and thus it’s fundamental to moral growth and responsibility. So I was eager to see what the theologian Paul Griffiths had to say about it. I disagree with Griffiths about much, but he’s always an interesting thinker and writer. This book is interesting, though I also found it frustrating for reasons you can read about in my essay. His central idea is that regret is “otherwise-thinking,” wishing that something were otherwise. He’s right, of course, but I don’t think his approach can adequately account for very large or very small regrets. I have been pleased to hear people tell me this review is a good essay in its own right; I hope you’ll agree: https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/sorry-your-loss.

A very short essay in America magazine on what the coronavirus pandemic has taught us about the American workforce. Basically, it has taught us a lot about how our conventional wisdom about work and dignity are almost entirely backward. To summarize the essay would be almost to repeat it, since it’s so short, so I will just encourage you to click and take one minute to read it: https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2021/02/15/what-coronavirus-taught-us-catholic-american-workforce-239982.

I live in Dallas, where most people have had sporadic electricity and heat during an unusually cold spell. I have been thinking about Thoreau, who wrote that “The grand necessity, then, for our bodies, is to keep warm, to keep the vital heat in us.” Food, shelter, clothing, and fuel all aim to fulfill this need. I normally take all four for granted, but they have all become questionable this week, their importance made salient by virtue of their precarity. My wife and I have made it through so far with the help of generous friends who were lucky enough not to have lost power. I am incredibly grateful to them.

Thoreau writes in Walden that we need to economize (“Simplify, simplify!”), to want much less, in order to keep warm more efficiently. “How can a man be a philosopher,” he asks, “and not maintain his vital heat by better methods than other men?” Thoreau thought we could each go it alone in this effort. While I generally appreciate Thoreau’s project of stripping away desires so as to maintain his vital heat, it’s become obvious to me this week that we often need to rely on others to stay warm. Mutual support is often the best means to meet the grand necessity. It, too, is a philosophical endeavor.

Please share this newsletter with your friends, family, coworkers, enemies, etc., by clicking the “Share” button at the bottom of this email. As always, thank you for reading.

Jon