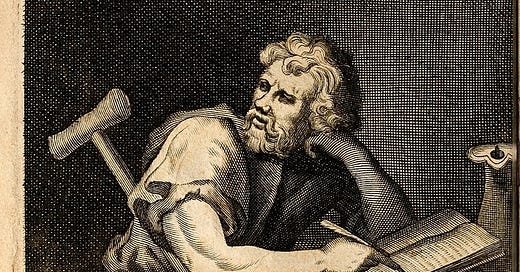

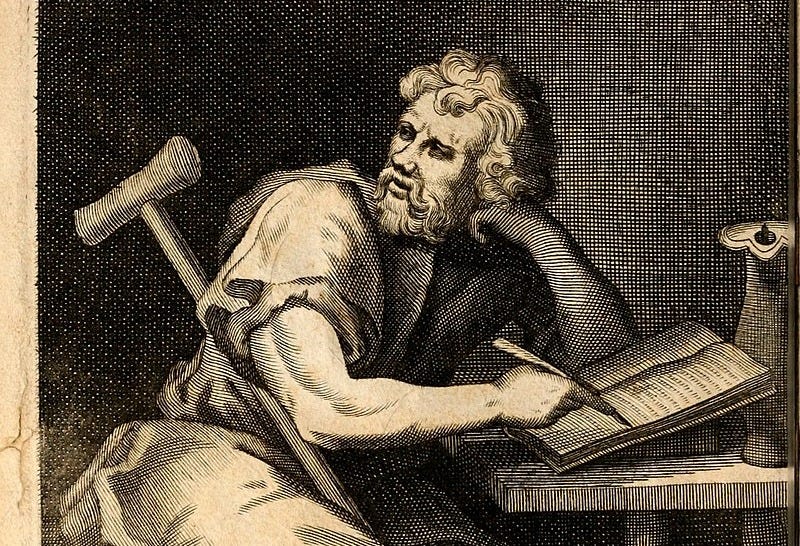

The first sentence of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus’s Handbook is, “Some things are up to us, and some things are not up to us.” It’s a tautology — in a logical sense, it’s trivially true, like “It is what it is.” In that sense, it’s hardly worth saying at all.

And yet: I think “Some things are up to us, and some things are not up to us” is a great and wise statement. I have to remind myself of it all the time. Epictetus says it in order to set up his recommendation that we invest our care in things that are up to us and become indifferent to those that are not up to us. So: Don’t get too worked up about the motion of the planets. They are not up to you. Don’t bet on sports — or, if you do, don’t pat yourself on the back when you win money, and don’t get upset when you lose. Neither outcome was up to you. Don’t worry about your reputation; that’s other people’s problem, not yours.

Instead, care about the things within your locus of control: Your actions and your state of mind.

There is much to criticize about the stoic point of view. A big part of a good life, I think, has to do with your interpersonal attachments. Epictetus cautions against such attachments, because the people you love will change and ultimately die (not up to you), and you’ll be upset. Even so, it’s worth it to be attached to them.

About a year ago, I wrote a couple of posts about something I called “liberal nihilism,” which is a form of self-imposed helplessness in the face of the supposedly immovable oppressive structures of the world. My idea what that a lot of well-intentioned people over-describe the forces of oppression in the world out of concern for the downtrodden. But when you say, over and over, that racism or patrarchy or capitalist exploitation are always and everywhere crushing the people beneath them, you leave yourself little room to mitigate these forces. If the world is as these well-intentioned folk describe it, then why bother trying to improve things? It won’t do any good.

Last week, Rachel M. Cohen wrote a very nice essay for Vox about this problem and its possible solution. A decade or more ago, Cohen wtites, she was highly engaged in movements for social change. But over time, she began to hear criticism of the small-scale work she had been doing:

Different arguments began to emerge: Volunteering, donating, and modifying one’s personal behavior were, at best, unproductive; at worst, they were harmful distractions from the change we really need. Be wary of those tote-bag shoppers at Whole Foods, championing recycling and reducing one’s carbon footprint. Didn’t they know that BP coined the idea of the “carbon footprint” to shift blame off its own oil production? Didn’t they understand that “lifestyle politics” was not the answer? Volunteering or bake sales didn’t threaten the status quo. They were what people in power wanted you to be doing.

The result of this message taking hold wasn’t that people abandoned ad-hoc volunteering in favor of well-organized mass movements. The result was that they abandoned working for change at all. (On cue, Le Tigre’s 2001 song, “Get Off the Internet” just came on the radio. Lyrics: “It feels so 80's / Or early 90's / To be political. / Where are my friends?”)

This mode of thinking creates a vicious cycle: You describe the problems as gigantic and systemic, so you think you can’t do anything about them, which only further entrenches the problems.

To break this way of thinking, Cohen decided to start donating and volunteering more. Did it solve gigantic problems? No. Did it solve small problems? Yes. And it made Cohen feel good, connected her with others, and gave her a sense of efficacy. Donating blood or working in a food pantry really helps people. It’s not a distraction from bigger-picture problems. It’s still possible to keep the systems in view as you take small actions.

Or, as was often said during the embarrassing, naive 1990s, “Think globally, act locally.”

I think it’s fair to say that Cohen is responding to a broad-based failure to accurately differentiate between what is up to us and what is not up to us. “Ending patriarchy” is not up to you, but, if you happen to work in corporate HR, writing a paid family leave policy that you think your company’s board will accept might be.

I think this distinction also broke down more than two years ago regarding the war in Ukraine — something I wrote about when the war began and U.S. liberals were evidently watching war coverage nonstop, out of a sense that if they looked away, the tide would turn against the heroic Ukraine fighters. But the success of Ukraine’s army is not up to you. It’s appropriate to mourn their losses and hope for their victory, but beyond that, you have your own immediate concerns to attend to.

It’s probably sometimes true that small actions can distract from the big picture, as activists claimed a decade ago. But I think that, more often, the big-picture things beyond your control distract from the smaller-scale things within your control. The first step, in any case, is to be clear about which is which.

I leave it as an exercise for the reader to determine how this principle applies to other issues of public concern.

Coda: The truth is, I haven’t heard as many expressions of liberal nihilism in the past few months as I did a year, two, three before. Maybe I’m not paying attention. But especially since Kamala Harris became the Democratic nominee for President, U.S. liberals seem to have a stronger faith than they did before.